How Trump’s Tariffs Will Boost GDP Permanently

Can America Pass the Marshmallow Test?

The Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) released a report on June 4, 2025, outlining how President Trump’s tariffs will impact the U.S. budget and economy.

President Trump is celebrating—even the democrat-controlled CBO is forced to admit that tariffs will help reduce the deficit over the next ten years.

President Trump is right: tariffs will help reduce the deficit one way or another. Either they will do so because they will raise additional revenue directly—tariffs are a tax, after all—or tariffs will raise revenue indirectly by reshoring America’s industry and growing our GDP.

History shows us that we will get a bit of both. However, if President Trump holds the line and ensures the tariffs remain high and stable, then we have the opportunity of a lifetime to reindustrialize America, rapidly grow our GDP, and create a prosperous future for our grandchildren.

The Infamous Marshmallow Experiment

In the 1960s Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel conducted a ground-breaking experiment on willpower and self-control. The premise? How long could children resist eating one tasty marshmallow, in exchange for two marshmallows in the future?

The marshmallow experiment taught us a surprisingly large amount about ourselves. For example, children who were able to delay gratification were typically more intelligent and were more economically successful in life. The experiment has been repeated on animals, with the most intelligent animals—like crows—typically showing a preference for delayed gratification.

Delaying immediate gratification—enduring short-term pain—in exchange for long-term gain is the key to building a business, being a successful investor, and running a successful country.

This brings us to tariffs. Tariffs are the short-term pain that we must endure for long-term gain. This is our marshmallow test.

Here’s the good news: if we hold the line, we will get our reward. The economic logic and historical evidence prove that tariffs will increase GDP and create jobs in the long run.

Mirror, mirror on the wall

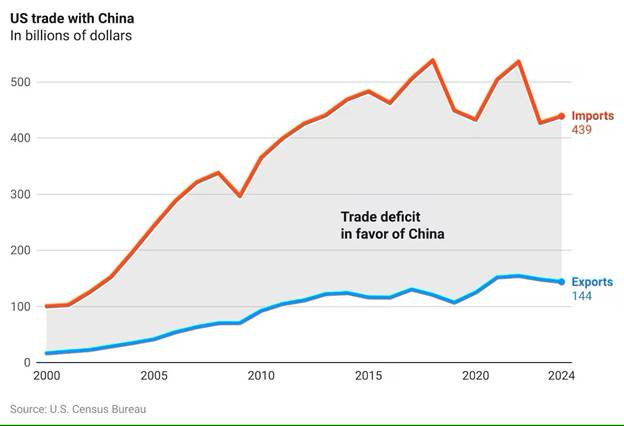

In 2024 America’s net trade deficit was $918 billion. This means that American consumed this much more than we produced. Of course, someone had to make these goods—mostly China. Accordingly, the trade deficit literally represents the value of America’s displaced economic production—if we didn’t buy it then we’d have to build it.

Reshoring the production that is currently reflected in the trade deficit will—by definition—increase America’s GDP by a commensurate amount.

We can expect America’s production (supply) to rise to meet our consumption (demand), because demand drives supply—that’s just how it works. Here’s the underlying logic:

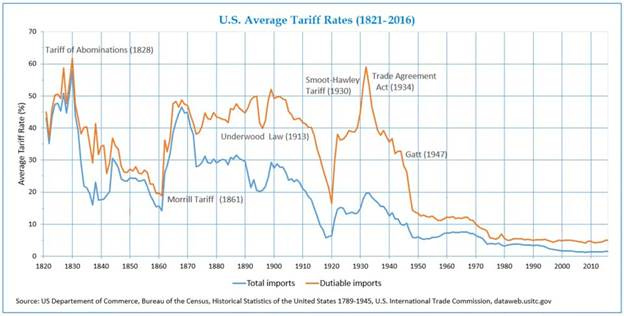

First, this has historically been the case. For most of its history America had extremely high tariffs which largely prohibited imports. Nevertheless, both GDP and national consumption grew well above the global average until America embraced global “free trade” in the 1970’s. In fact, America’s economy growth has never been slower since we abandoned tariffs and closed the gold window.

Second, industrial production is subject to increasing returns on investment. This means that the more we make of a product, the cheaper each unit of product becomes. The logic of increasing returns implies that at a certain level of consumption, the cost difference between American and Chinese goods would disappear. Paradoxically, part of the reason that Americans find Chinese production “cheap” is because we are not producing enough ourselves.

Third, Americans pay for the trade deficit by selling assets and promising debt. These financing options would remain open to Americans in a closed system, and therefore it is logical to assume that American consumers would continue to take full advantage of them. True, they may not get as much “bang for their buck”, but that is a short-term problem. Ultimately, Americans are happy to spend as much as possible, no matter where the production originates.

Fourth, America is nowhere near its full production potential. In reality, tens of millions of Americans are unemployed, and many hundreds of billions worth of formerly productive assets are currently idle. America certainly has the economic spare capacity to increase production to match consumption, provided that the economic incentives were in place—or perhaps more appropriately, the disincentives were removed.

Essentially, America has production capacity to spare, and it could quite easily be scaled-up to meet our own needs. America survived as a largely self-sufficient country for nearly two centuries, and could do so again.

Fifth, the desire to consume logically precedes the desire to produce—not vice versa. It is simply a truism that man makes because he wants. A hungry man will hunt, or fish, or farm. It is his desire to consume that drives his food production. It is not his love of reaping wheat or shucking corn that motivates his backbreaking labor. Work—production—is a means to an end. It is not the end itself.

Consumption drives production.

In an open economic system—one where nations trade freely—it is possible to consume more than you produce. However, if the system were to close, we can deduce that production would rise to match consumption. Not vice versa.

This logic virtually guarantees that the trade deficit displaces America’s potential GDP: rather than build it, we buy it. Therefore, running a trade deficit must reduce GDP.

President Trump’s tariffs will reduce the trade deficit. In doing so, they will increase GDP by a corresponding amount, and reshore the jobs that have been lost to China and Friends, as I explain in my book: Reshore, How Tariffs Will Bring Our Jobs Home & Revive the American Dream.

Tariffs will make America rich again—but not immediately. Will the American People pass the collective marshmallow test? I hope so.

We need to be patient and remember that America does not just belong to us: it belongs to our children, our grandchildren, and every generation that has come before or after us.