Sunday Classic I: Debunking 'Guns, Germs and Steel'

Jared Diamond's Magnum Opus is a Side-Show

Author’s note:

I hate writing de novo. This is the artist’s domain. Political commentary should be just that—commentary.

I am at my best when I am in conflict with someone, or some idea. To that end, I will be writing long-form commentaries that will engage directly with someone else’s work or idea. I will publish these on Sundays, and will do my best to write at least two per month.

God bless. SPM.

The ur question of socio-economics is: why are some countries rich and other poor?

Many solutions have been proposed. For example, in 1748 Charles de Montesquieu wrote De L’Espirit des Lois. Montesquieu observed that countries located in temperate latitudes were typically richer than those located in tropical latitudes. From this, Montesquieu hypothesized that climate and geography helps explain why some nations are rich and others are poor.

Many classical liberals and leftists have been allured to the “geographic” explanation for the wealth of nations. Why?

Because it entirely sidesteps less “politically-correct” explanations like racial differences in intelligence, cultural chauvinism, or the Faustian spirit. It offers an easy way out. Why is Europe rich? Environment. Why is Africa poor? Environment.

Jared Diamond’s book Guns, Germs, and Steel stretched Montesquieu’s observation into an all-encompassing thesis, arguing:

The striking difference between the long-term histories of people of the different continents have been due not to innate differences in the peoples themselves but to differences in their environments.

That is, Europe is rich and Africa is poor because of environmental differences as they were in place 11,000 years ago. Essentially, mankind’s historical development is predetermined. We are all simply beneficiaries—or victims—or our ancestral geographic circumstances.

Not only is this thesis soothing to the anxious and soft liberal constitution, it has the added benefit that it explains history as being entirely materialistically determined—there is no room for the spirit of a great man—or for the divine spark.

Matter moves according to the simple chain of cause and effect, and this plays out ipso facto: the history of mankind is simply the great ballet of physics. We are a dance of molecules. This is no doubt comforting to the godless—who I assume are Diamond’s primary acolytes.

While there is no question that Diamond’s book is assiduously sourced, his overall thesis falls flat.

Instead, reality leaves us a paradox—a paradox that is unraveled for the first time in my book Reshore—that environment simultaneously matters and does not matter whatsoever.

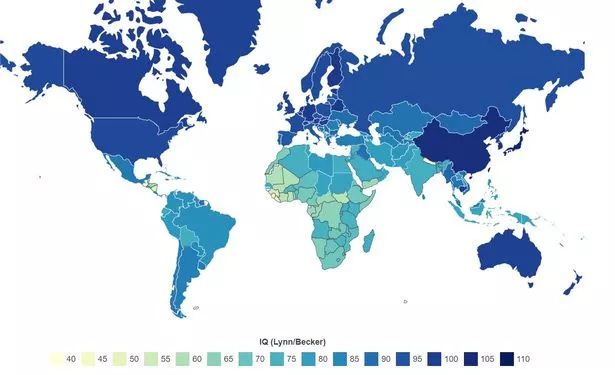

Now, it is a fairly simple task to “debunk” Diamond’s thesis by pointing to more compelling explanations of economic disparity. For example, many readers would no doubt be satisfied if I simply posted the below national IQ map and said this was a better explanation, therefore there’s no point in engaging with Diamond’s environmental explanation:

While it’s true that national IQ scores do explain the phenomena better in aggregate, bringing this up is in fact a red herring that does little to explain why environment is inconsequential.

It’s also more interesting to engage with the environmental explanation of the wealth of nations on its own terms.

On Guns, Germs, and Steel

Diamond attempts to answer the question: “why did wealth and power become distributed as they are now, rather than in some other way?” Implicitly, the question can be framed as why did Europe conquer the world, and not vice versa?

Diamond explicitly rejects any inherent differences between peoples as a valid explanation. This alone should leave us skeptical of his work, but let’s engage Diamond on his own terms.

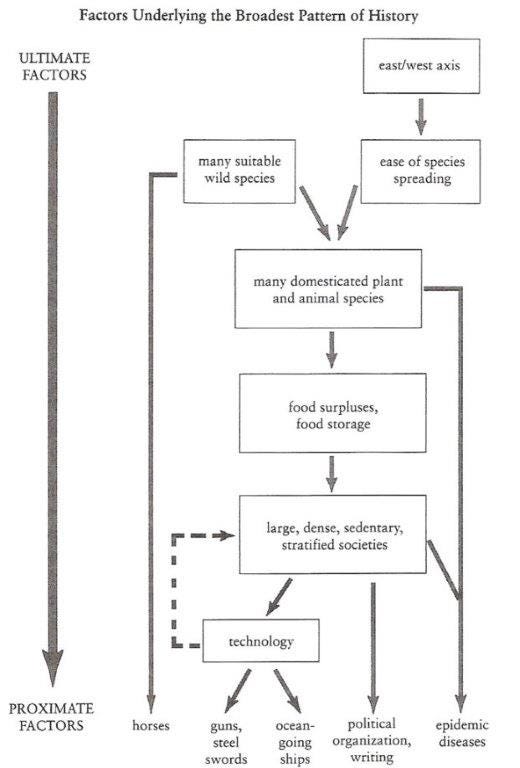

His train of through is summarized in the below chart, taken from his book:

The logic runs as follows:

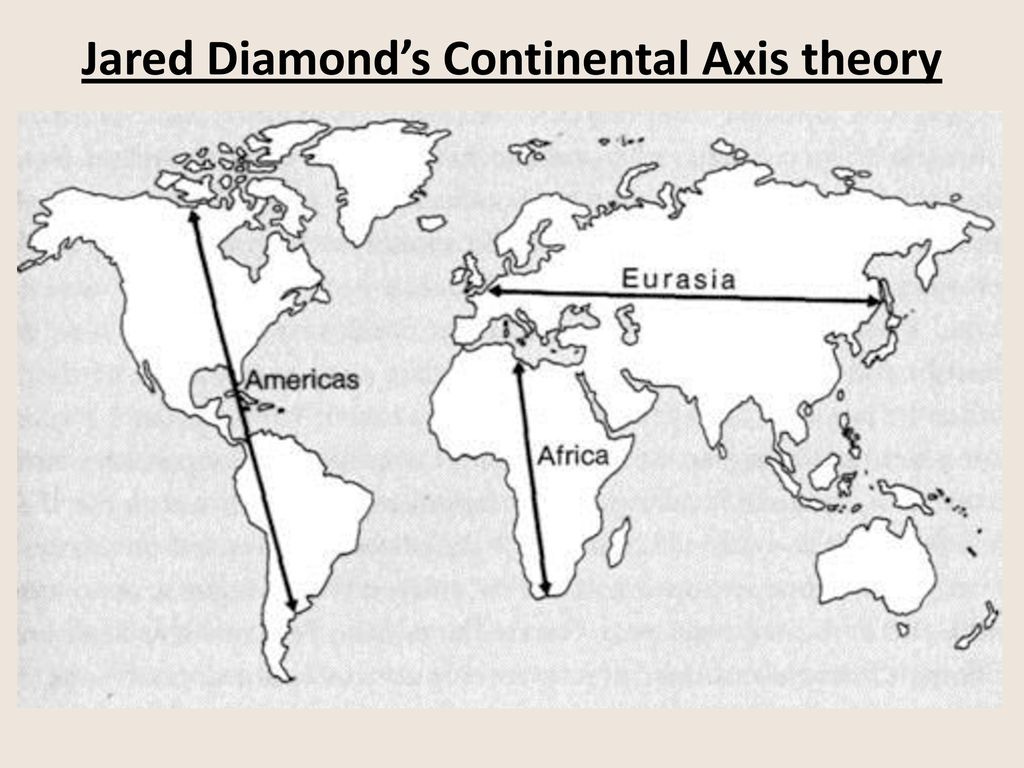

First, the world is divided up into a number of different continental axes. A continental axis is an geographical area along which people, animals, and ideas can travel relatively unhindered. In general, these areas are contiguous, devoid of major geographic barriers (like a sea, or impassable desert or mountains), and climatically congruent.

There are three main relevant axes which birthed ancient civilizations, being: the Eurasian Axis (Western Europe to East Asia), the African Axis (the Sahel to the Ethiopian Highlands), and the American Axis (Mesoamerica to the Great Plains, and the Pacific to the Andes).

Second, certain axes had more flora and fauna available for domestication, and the longitudinal length of the axis facilitated the spread of agricultural, population, and later technology.

Third, domestication and more efficient food production led to a population explosion. This, in turn, led to societal stratification—a portion of the human population was freed from the need to produce its own food, and could therefore focus on higher or more abstract pursuits, such as warfare, art, religion, or learning.

This resulted in technological growth. Again, the diffusion of technology over the various axes is important to understanding why the Eurasian Axis outperformed the others—it was home to the most people, and provided the easiest means of transmitting technology. Enter guns & steel.

Fourth, the domestication of many animal species—in particular pigs and poultry—led to diseases jumping from animal to man. In addition to killing a great many people, the benefit was that the survivors had strong immune systems. This was not true for peoples who did not extensively domesticate animals (like the Mesoamericans or Australian Aborigines). Enter germs.

Basically, Euroasian civilization(s) dominates the world because it benefited from the above environmental accidents—a long east-west axis and many domesticable plants and animals, which set in motion an inexorable chain of events.

But as always, the Devil’s in the details. The question we need to ask ourselves: are Diamond’s presumptions true? No.

False Premise 1: Eurasia’s Continental Axis is Relatively Permeable

Diamond argues that the Eurasian Continental Axis stretches from Western Europe to Eastern Asia along a relatively temperate zone. This allowed the spread of crops, livestock, and ideas along the entire length of the axis.

Diamond alleges that this was a massive benefit to Eurasian civilizations—they benefitted from trade and discoveries along the entire axis. Bigger is better.

This is contrasted to Africa, as the continent runs along a north-south axis, and therefore separates the population along different climatic lines. The same is true of the Americas, which are longer than they are wide.

This allegedly stymied the transmission of agriculture, domestication, and technology, retarding the growth of civilizations. Basically, the north-south axis of Africa and the Americas created civilizational “islands” which were left to their own devices. The same logic applies to Australia and Oceana.

This makes some intuitive sense. However, Diamond’s own research undermines his argument.

For example, Diamond waxes on about how writing was such a transformative invention that it was only invented a few times in history—almost all civilizations received the technology through transmission. Diamond notes that writing arose independently in Sumer (3000 BC), Egypt (3000 BC), Mesoamerica (600 BC), China (1300 BC), and Easter Island (1700 AD), although I note that the latter’s independence is contested.

If the Eurasian Axis were as permeable as Diamond claims, why did Eurasians invent writing independently three times over? Surely, such a transformative invention would have been invented once, and then spread throughout the entire axis due to its high utility. Instead, it appears that contact was so limited that writing developed independently in Egypt and Mesopotamia, which are less than 1,000 miles apart!

Although Diamond focuses on the prehistorical period, it is clear that the West and China remained separately civilizations, with very limited contact, until well into the historical period. This is why numerous significant inventions, such as black powder and moveable type, were invented independently in Europe and China.

Diamond’s premise is also undermined by the fact that most major Eurasian domestic animals were domesticated independently, multiple times. For example:

Cattle were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent (c. 8000 BC) and the Indus Valley (c. 7000 BC)

Pigs were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent (c. 9000 BC) and China (c. 8000 BC).

Chicken were domesticated in the Indus Valley (c. 3000 BC) and also Southeast Asia (c. 6000 BC) and possibly China.

Sheep were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent (c. 9000 BC) and possibly also in Central Asia and Europe.

Goats were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent (c. 8000 BC) and likely also in the Indus Valley region (c. 7,000 BC).

Horses were domesticated on the Pontic Steppes (c. 4,000 BC), although there is genetic evidence that they were also domesticated separately in Iberia (c. 3,000 BC).

Cats were domesticated in the Near East, possibly Cyprus (c. 7500 BC) and also in China (c. 3000 BC).

Based on animal domestication, it appears that there were three main regions which were relatively disconnected from one another in the material period (~11000 BC): the Fertile Crescent, the Indus Valley, and China. Interestingly, these three regions birthed the three major civilizations of Eurasia: Western, Indian, and Oriental.

In terms of the functional length of these axes, the African Sahel axis is actually as long or longer than the three sub-Eurasian axes, which clearly operated as independently as the African.

False Premise 2: Africa’s Continental Axis was Relatively Impermeable

Diamond contrasts the supposed ease of transmission through Eurasia with the difficulty of transmission through Africa—as if the Sahara is any less impenetrable than the Gobi, or the Ethiopian highlands were more impassable than the Himalayas!

In any case, it is impossible not to observe that Africa is literally connected to Eurasia, and there was significant historical trade along the Nile River and along the East African coast. Nubians, for example, were certainly in meaningful contact with the Egyptians—even building funeral pyramids of their own, as seen below:

Likewise, although Swahili is a Bantu-based language, it has incorporated significant number of Arabic loan-words (about 40% of its vocabulary). Swahili is to Arabic what English is to Latin—and certainly no one would pretend that English was not influenced by Latin.

It’s also worth noting that Africans were already resistant to Eurasian diseases when Portuguese traders began arriving to trade in the Fifteenth Century.

Even across the Sahara there appears to be meaningful cultural exchange. Consider the proliferation of Islam into the Sahel. Notably, King Mansa Musa of Mali was acknowledged as amongst the richest kings of his time, and during his pilgrimage to Mecca, he set of an inflationary crisis (having spend so much gold on the way), that it took 10 years for markets to go back to normal.

Africa was clearly permeable to a degree that is minimized by Diamond to “prove” his flimsy thesis.

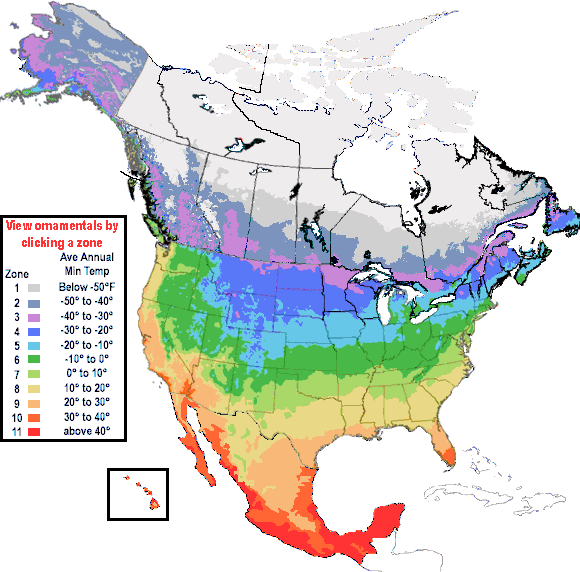

False Premise 3: the American Axis Runs North-South

Diamond’s handling of the Americas—particularly North America—is bizarre. He claims that the Continent(s) runs north-south, and accordingly there is less ability for agricultural, technological, and cultural spread than there was in Eurasia.

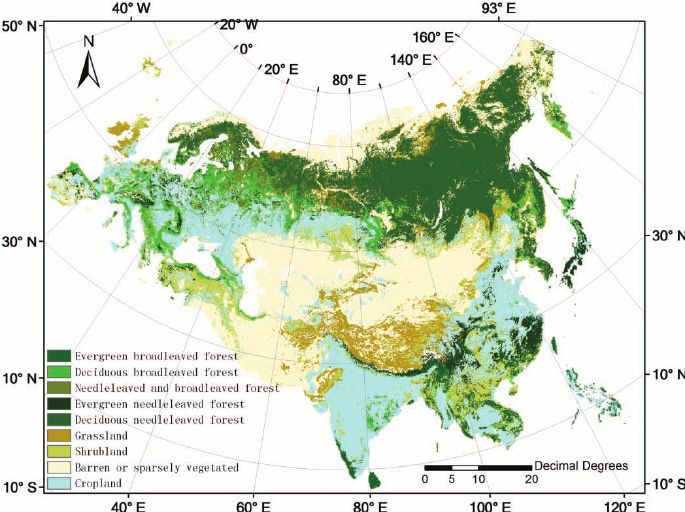

This is patently false. Looking at North America, we can see that the growing zones flow smoothly across the continent. That is, crops that grow relatively well at one latitude and be expected to grow relatively well at roughly the same latitude all across the continent. North America is, actually, a very blessed continent in terms of its environment.

This is very different than Eurasia, which is punctuated with huge regions whose climate is carved into chunks by large arid and mountainous regions that impact the spread of flora and fauna—as noted above.

In terms of scale, the North American continent, from the Atlantic to the Rockies, provides an axis comparable in scale to those found in the old world.

Further, Diamond’s axis model breaks down when you realize that the Mesoamerican axis the Mesoamerican axis was 500 miles wide, and the Andean axis just 300 miles wide—that’s if we assume that Diamond is right to ignore the rest of North America’s easily habitable and traversable terrain.

Nevertheless, Mesoamerica and the Andes produced relatively advanced civilizations like the Maya, Olmecs, Toltecs, Aztecs, and Inca, who were arguably more advanced than most sub-Saharan African civilizations.

Diamond cherry picks his evidence to fit his theory.

False Premise 4: the Initial Conditions Determine Present Conditions

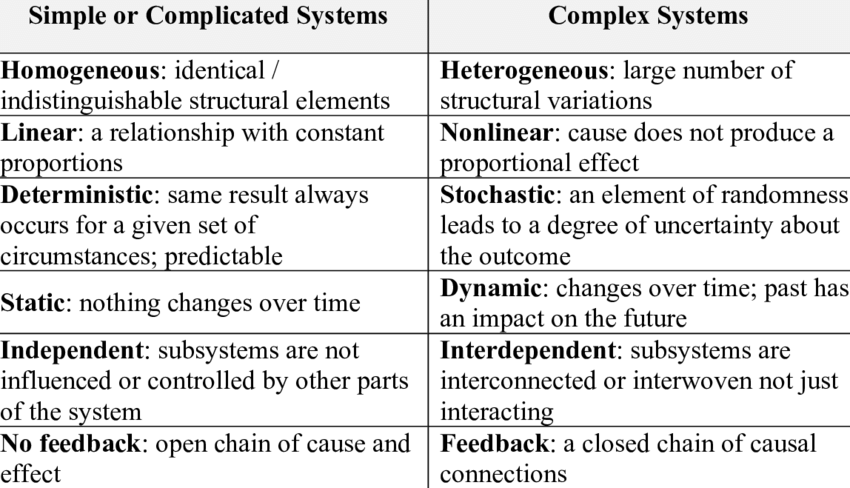

Diamond’s biggest error is assuming that initial conditions determine future conditions. This logic works only when dealing with simple systems—like machinery or a billiards table—but not when dealing with complex systems.

Civilization is clearly a complex system, therefore, the initial conditions are not determinative of present outcomes.

In more detail: a simple system is a mode of order wherein cause and effect are related in a linear, one-to-one, way. That is, if you know the starting position of each systemic element, and you know what causes applied to said system, then it is possible to predict—with certainty—the outcome.

A classic example of a simple system is a billiard’s table. There is a one-to-one relationship between the cause, the direction and speed of the cueball, and the effect, the direct and speed of the 8-ball. Because of this, it is possible for the skilled player to know the outcome of a shot before he takes it. The same is true for most artificial modes of order, be it the game of chess or the operation of a washing machine.

On the other hand, a complex system is a mode of order in which cause and effect are related in a non-linear way. That is, a single cause may have multiple effects on the system, and these effects may themselves interact with each other in novel ways.

Complex systems are subject to feedback loops, and may manifest emergent properties at different scales. As such, knowing the starting position of each systemic element, and the forces applied to said system, will not allow you to predict the outcome with any certainty.

That said, it is possible to forecast the probability of various end states.

A classic example of a complex system is the weather. There is a non-linear relationship between the various inputs, such as level of solar activity, humidity, wind speed, and the end result—which is a 30% chance of blue skies and a 70% chance of thunderstorms. It is not possible to know a priori what the weather will look like next week. At best, meteorologists and make and continuously-update forecasts based on the best-available data. The same is true for many organic and natural systems, be it human history or a hurricane.

Civilization is a complex system. In fact, it is the most complex system.

Consider that the causes of weather patterns are the interplay of solar radiation and water droplets. These causes are simple causes which, when isolated, operate in a linear way. These interactions are complicated to the point that a priori knowledge is impossible—but this is nothing compared to civilization’s complexity.

Civilization is the manifestation of a nearly infinite number of individual choices—the exercise of deliberate free will, of human consciousness. Philosophers disagree as to whether consciousness originates with God or is an emergent property of the human brain, but all agree that the mind is perhaps the most complex organic system.

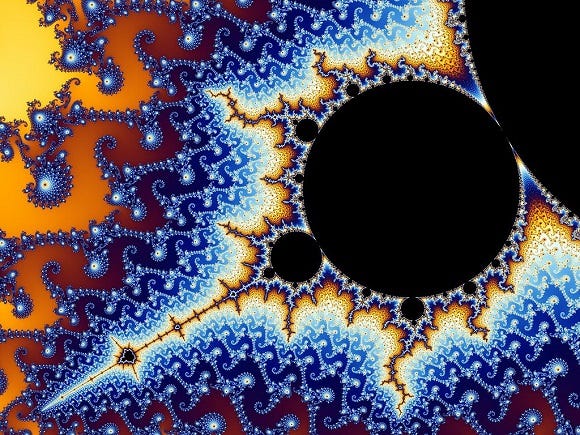

When this fact is combined with the fractal nature of civilizational organization—different layers of familiar, political, economic, and religious organizations make different decisions that have ripple effects between the layers—it becomes obvious that discussing civilization in a reductionist way is beyond incompetent.

To directly address Diamond’s argument: the fact that Eurasians—particularly Western Europeans—came to dominate global civilization may or may not have anything whatsoever to do with the “initial conditions” as of 11000 BC. While a point of interest, they are irrelevant and offer no explanatory power.

For example, one would assume, given that Diamond notes civilization appears to be an autocatalytic process, that those places with the oldest civilizations would likewise be the most advanced—but that is certainly not the case.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite: the newest civilization, being Western (particularly Anglo-Saxon) civilization is the most advanced.

Diamond’s Thesis Lacks Explanatory Power

Diamond’s analysis is somewhat interesting, but flawed.

Remember, Diamond set out to answer why Eurasian civilizations—in particular European civilization—outperformed everyone else. He says this has nothing to do with innate differences between the peoples, but due to differences in their environment. His analysis focuses primarily on the initial conditions as they were 11,000 years ago. From that point on, the march of history was inevitable.

Does his explanation provide a satisfactory answer to this question? No.

Not only is there no such thing as a coherent Eurasian civilization—there are at least two, probably three, distinct Eurasian civilizations—but his thesis is little more than post hoc reasoning. His hypothesis is a “just so” explanation of our current paradigm which has zero predictive power.

Overall, Diamond’s work is just intellectual masturbation.