Tariffs are for Computers, Not Copper

Raw Material (Banana) Tariffs are for Banana Republics

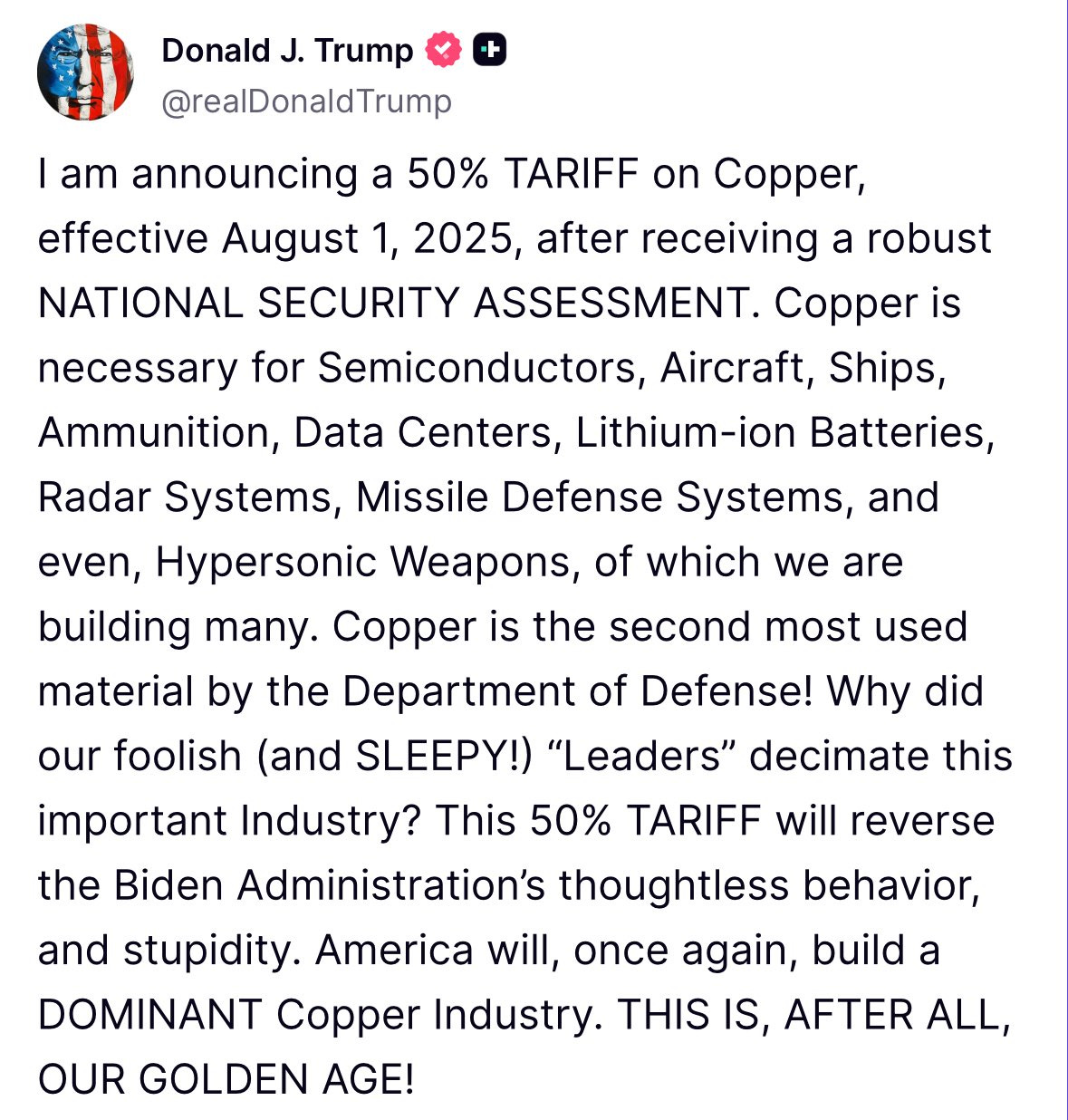

On Tuesday, President Trump told reporters he plans to raise tariffs on copper to 50 percent. Copper futures surged by 17 percent shortly afterwards—the largest intraday gain since at least 1988.

Many will make—or lose—a small fortune on Wall Steet in the coming days and weeks. No doubt, the winners will gas-up the Presidency for protecting America’s economy: tariffs are good! Meanwhile, the losers will accuse him of economic illiteracy: tariffs are bad! Which is it? Are tariffs good or bad?

The answer: both.

Tariffs are good when they promote economic growth or economic self-sufficiency. If not, then tariffs are just another useless tax.

Tariffs on copper accomplishes neither of these objectives. In fact, tariffs on copper—like tariffs on any other raw or exotic material—hurts the economy and makes America less safe in the long run. That is not to say that maintaining supplies of copper is not important—it is—but tariffs are not the most efficient way to solve this problem.

On Hamilton’s American System

Alexander Hamilton published his Report on Manufactures in 1791. In the Report, Hamilton explained how protective tariffs should be used to protect American manufacturing from foreign, at the time European, competition. Hamilton believe this would be good for two reasons.

First, it was a question of national security. How could the United States defend her newfound freedom if she could not manufacture firearms or steel? Remember, the French provided the Colonies with over 80,000 firearms, without which the Revolution would have failed. For Hamilton, manufacturing was an existential necessity.

Second, Hamilton believed that a robust manufacturing industry was the key to unlocking wealth. This belief was well-founded. Remember, the Americans had lived under British rule for nearly two centuries. During this period, they observed how Great Britain enriched herself at the Colonies’ expense through a trade pattern called mercantilism, wherein Great Britain imported raw materials and exported manufactured goods.

Mercantilism enriched Great Britain at America’s expense. During the Eighteenth Century, Britain’s trade surplus with the Colonies grew from £67,000 (1721-30) to £739,000 (1761-70). Colonial demand fueled British industry and spurred the Industrial Revolution. Between 1700 and 1773, Colonial demand accounted for 72 percent of Great Britain’s manufacturing growth. During this time, manufactured goods rose from 4 percent to 27 percent of British exports, and by 1770 nearly 1 in 5 Britons worked in manufacturing.

As I explain in my book Reshore, this asymmetrical trade made Great Britain rich and set the stage for the Industrial Revolution and Victorian Age. Hamilton was eager to copy Britain’s strategy.

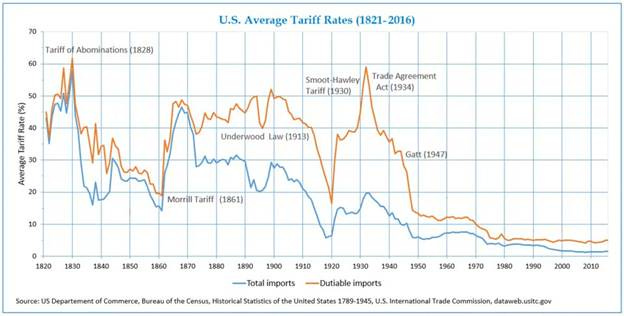

Thankfully, Hamilton’s recommendations were largely followed. Over the next century and a half, the United States prospered under the ‘American System’, which was essentially a less extractive version of British mercantilism. In fact, America had the highest average tariff rates in the world throughout the Nineteenth Century.

It was during this period that America industrialized and became the most prosperous country on earth.

Centuries of economic wisdom—learned through extensive trial and error—was thrown out at the end of the Second World War, and many of the last remnants of the American System were dismantled by 1973. Since then, America has run a large, chronic trade deficit. Well over 60,000 factories and 5 million manufacturing jobs were lost since 2001 alone.

This brings us to the ultimate question: what is the point of President Trump’s tariffs?

In my view, the calculus has not changed: it is still in America’s best interests to be economically self-sufficient; and it is still in America’s best interests to prioritize value-added economic production, over the extraction of raw materials. Basically, it’s better to be a country than a colony. But tariffs on copper accomplish neither of these objectives.

Banana Tariffs are for Banana Republics

Tariffs are good when they promote economic growth or economic self-sufficiency. If not, then they’re just another pointless tax. Does a 50 percent tariff on copper accomplish either goal?

The copper tariff will probably not grow the economy. In fact, it will probably hurt the very industries that the American System is supposed to support.

In 2024 America produced approximately 1.1 million metric tons of copper. Meanwhile, America consumed approximately 1.8 to 2 million metric tons. The gap—over 40 percent of copper consumption—was filled with imports. A 50 percent tariff would raise the price of copper.

To be fair, this also happens when tariffs are raised on the cost of manufactured goods. However, manufacturers are usually able to scale-up production relatively quickly. This is because the typical manufacturer operates at about 60 percent capacity, meaning there’s room for expansion. Also, manufacturing is subject to the law of increasing returns, meaning that each additional unit of production lowers the average production cost.

This is not true for copper production.

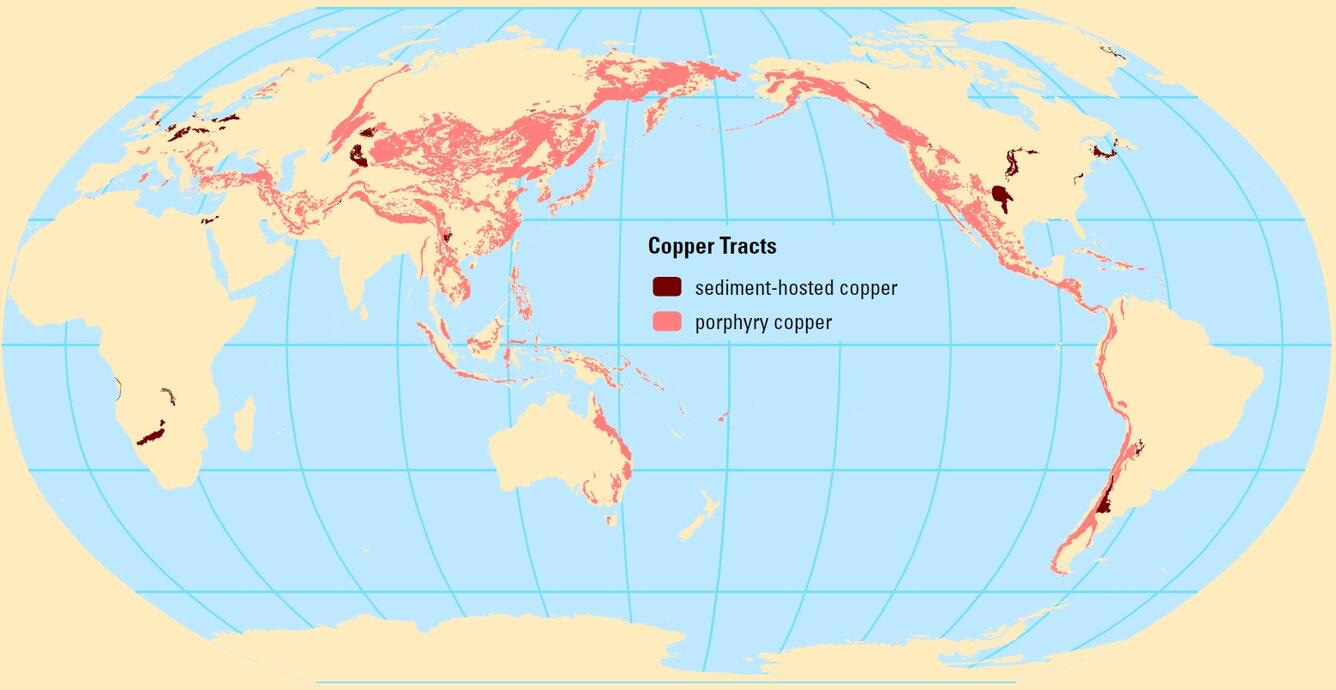

The reality is that mining operations take years—sometimes decades—to start production. Moreover, mines are typically unable to produce more ore without major capital investments. On top of this, the U.S. government imposes so many environmental regulations on mining (and recycling) operations that the domestic supply is almost inelastic.

And—I’ve saved the most obvious for last—tariffs cannot create economically exploitable copper deposits ex nihilo. Copper mines are where they are. Although the United States is blessed with ample deposits, these cannot be exploited due to the government’s own fiat. So which is it? Why raise tariffs without lifting the regulations?

In any case, if America cannot increase the supply to meet demand, the price of copper will increase. This will hurt American manufacturers—especially those producing electronics and advanced technology. As a result, the copper tariff will hurt the very industries that tariffs are supposed to protect.

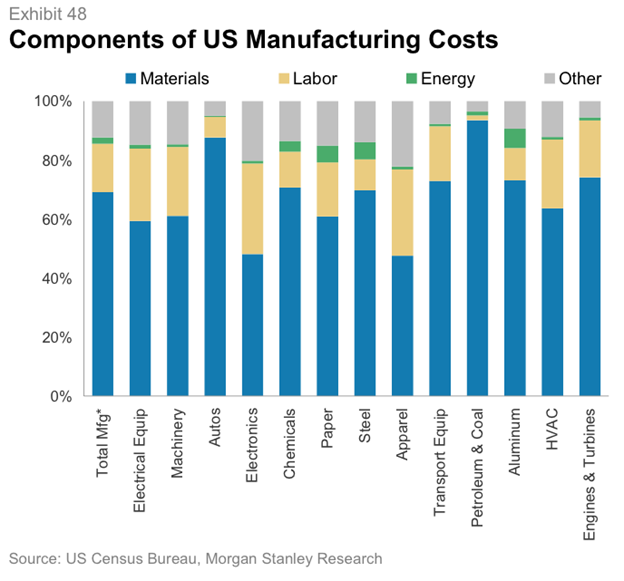

Worse still, American demand for imported copper will likely decrease. This may lower the global price of copper (once the heady day-traders have had their fill). This could, inadvertently, help Chinese manufacturers by reducing raw materials costs. After all, the cost of raw materials is the single largest input cost for manufacturing.

As for national security, there is no question that import-dependency on copper is a valid national security concern. However, tariffs are not the most efficient way of securing access to copper. In fact, they may be the least efficient way to solve the problem. Here are three better ways.

First, eliminate the regulations that prevent Americans from building and expanding copper mines in the first place. Do the same for recycling facilities, as up to 40 percent of America’s copper supply is from recycled copper (Basically, we send garbage electronics abroad, they are recycled, and then we buy the copper again).

This alone would probably solve the problem. Not only that, it’d be free & it would lower the cost of copper.

Second, we could expand the scope of the National Defense Stockpile (“NDS”). The NDS was founded in 1939. Its purpose was to ensure the U.S. had a critical stockpile of resources in case of conflict. Unfortunately, the stockpile is utterly gutted, and it’s been that way for decades.

President Trump could quite easily direct the NDS to begin buying copper—and other rare or critical raw materials—on the open market when prices are low, store them, and then sell them at or below cost to American producers when prices rise.

Just to be clear, this sort of program was administered successfully for nearly a century in Canada under the Canada Wheat Board (“CWB”)—and it had real and tangible economic benefits.

The CWB was created in 1935 to purchase wheat from farmers in Western Canada. This wheat was then stored and sold when wheat prices were highest on international markets. Further, the CWB’s economy of scale allowed it to tilt prices in Canada’s favor. Between 1935 and 2012 wheat sold by the CWB averaged 4 - 10% above market returns. On top of this, Canadian farmers saved 1 - 2% in financing costs, because the CWB guaranteed at least 75% ROI.

If it is possible for a government agency to beat the market by ~5% for 77 years, then I suspect it would also be possible for the DOD to undercut the market by a similar amount. That is, the NDS could use tariff revenue buy raw materials on international markets when the prices are low, or use its tremendous buying power to acquire discounted raw materials from developing countries.

This would have two benefits. First, supplying the NDS should be a national security priority—America needs adequate stockpiles of supplies in times of war. Second, once the stockpiles are full, the NDS could sell the raw materials at the discounted rates—functioning like the CWB in reverse. This would provide American industry with below-market raw material inputs, evening the playing field with China, and lowering the cost of living for the American people.

And before you accuse me of being a communist, that I am simply proposing to take full advantage of a program that has already been around for over 80 years. Also, remember that the late Milton Friedman proposed something similar to this in his libertarian manifesto Free to Choose. Why? Because there is simply no way for the “free market” to address the national security issues caused by global supply chains without reshoring production or stockpiling raw materials.

Given that we need to address this issue anyways, we may as well wring out some added benefits.

Third, we could simply use some of the tariff revenues to subsidize copper mines, to guarantee a secure level of output. This would be far cheaper than raising copper prices for the entire economy. President Trump has shown that he is not afraid to make these sorts of investments with his “Golden Share” in U.S. Steel—so why shy away from doing the same with copper?

Given the above logic, we are left with no choice but to conclude that the proposed 50 percent copper tariff is just another tax-grab—just like the tariffs on bananas and coffee.

President Trump needs to focus his attention on imposing tariffs that will create jobs and boost GDP. Tariffs on raw materials do precisely the opposite.

Spencer some may not like this article and the finer critiques, but thank you for being a straight shooter.